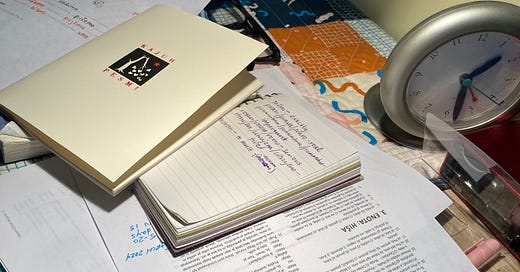

Vsak dan študiram slovenščino. Slovenski jezik je izjemno zahteven. Nisem zelo dobro v tem. Vem malo, razumem manj. Moji staveki so preprosti. Naredim veliko napak. (Zdaj naredim napak, sem preprična.) Ampak vztrajam. Moram vztrajati. Zakaj? To je res, učiti se pomeni boriti se. Vsak dan.

Torej mora biti ljubeče dejanje.

Every day, I study Slovene. The S…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to derailleur to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.